Article by Matthew Denholm, courtesy of The Australian.

30.10.2025

Farmers across the world are demanding a more nuanced approach to tracking and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, saying livestock must stop being a “whipping boy” for global warming.

Peak meat producer bodies from 11 key nations will on Friday demand governments globally follow New Zealand and Uruguay in treating methane from livestock and other emissions separately via “split gas reporting”.

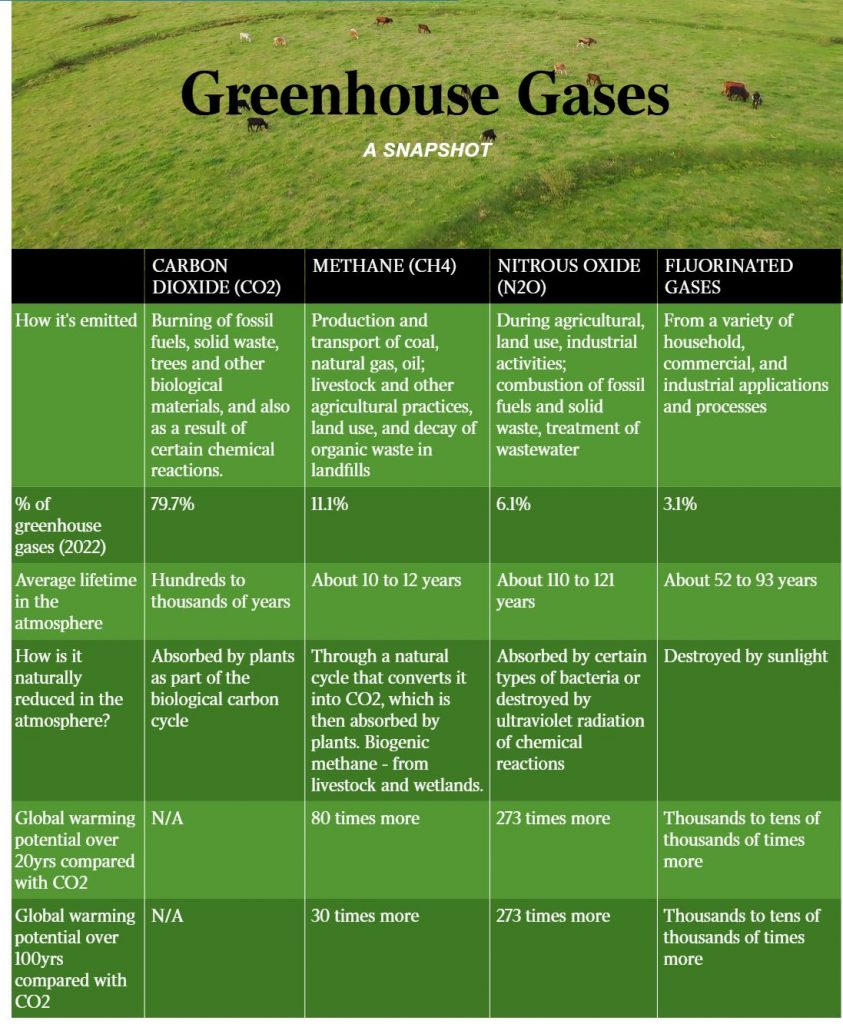

They argue the current widespread approach of expressing livestock methane emissions as a carbon dioxide equivalent overstates the warming effect of this gas by three to four times.

Carbon dioxide produced by burning fossil fuels lasts in the atmosphere for 1000 years, whereas methane from grazing animals is broken down in 10-12 years as part of a “constant” or “biogenic” carbon cycle.

“We need to separate those gases that are occurring in a cycle, and always have been, versus new carbon being injected into the atmosphere from fossil fuel burning,” said Adam Armstrong, partner in NSW and Queensland-based cattle producer Russell Pastoral Operations.

“We’re getting blamed for the climate crisis despite doing nothing different than has been going on forever, in a cycle that’s been in balance for millions of years.

“By some estimates, there are less ruminants in North America now than there were before it was settled (by Europeans), when there were 80 million buffalo running across the Great Plains.”

This frustration that emissions accounting and targets effectively place cows and cars “in the same basket”, is shared by meat producers and some scientists globally.

They fear it will lead to unnecessary, counterproductive reductions in meat consumption and herds and not maximise agriculture’s role in cutting emissions.

The declaration calling for a split gas approach is signed by Cattle Australia and peak groups from Canada, the US, Britain, NZ, South Africa, Ireland, India, Cambodia, Georgia and Kenya.

They say cattle farming can play a major role in reducing methane emissions through methane-cutting feed additives, selective breeding for lower-emitting cattle, improved manure handling, and by managing grazing to boost soil sequestration.

“We are very much the solution to this climate crisis – not the problem,” Mr Armstrong said.

NZ earlier in October endorsed such a position, announcing a separate and lower methane emission reduction target – of 14 to 24 per cent below 2017 levels by 2050 – and $NZ400m in methane-busting measures.

The joint statement by the meat industries of the 11 nations calls on all parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change to adopt a similar split-gas approach.

They say this would not necessarily impact net-zero strategies. “The science is clear: emissions of long-lived gases must reach net zero by reducing as far as possible, and then balancing with carbon storage or removals to prevent further warming,” the statement says. “In contrast, emissions of short-lived gases, like biogenic methane need only to decline gradually to have the same effect.

“This fundamental difference in behaviour needs to be recognised in climate policy, and adopting a split gas approach is the most effective way to do so.”

Cattle Australia, one of the signatories, is lobbying the Albanese government to follow NZ and Uruguay in adopting the approach. “The reduction of emissions and their effect on global warming cannot come at the expense of food security,” Cattle Australia chief executive Will Evans said. “So we’re trying to get an accurate set of data so that we can make sure we’re not limiting production but are reducing emissions intensity.

“We’re not wanting to shirk responsibilities or get out of anything. This is about getting accurate measurement and we’re optimistic the government will see it that way.”

A spokesman for federal Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen suggested the government was unlikely to budge from its exclusion of split reporting from Australia’s Net Zero Plan and formal Paris Agreement target. “The government has accepted the independent Climate Change Authority’s advice to set national greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets that cover all greenhouse gases, including methane,” he said.

Even the Coalition – deeply divided over climate change policy – appears uncommitted, backing detailed biogenic methane accounting while not explicitly endorsing a split gas approach to targets.

“The government should be developing accurate methane emissions accounting frameworks and metrics, to enable emissions to be accurately measured and demonstrated for the livestock sector,” said Nationals leader David Littleproud.

Livestock industries are urging countries to support a split gas approach as part of a review by the UNFCCC to be conducted by 2028.

Australia’s beef industry on Thursday reported it had reduced net CO2-equivalent emissions by 70 per cent since 2005, largely driven by carbon sequestration on grazing land.

Scientific studies differ on whether there are more or fewer ruminants in North America now than pre-European settlement.