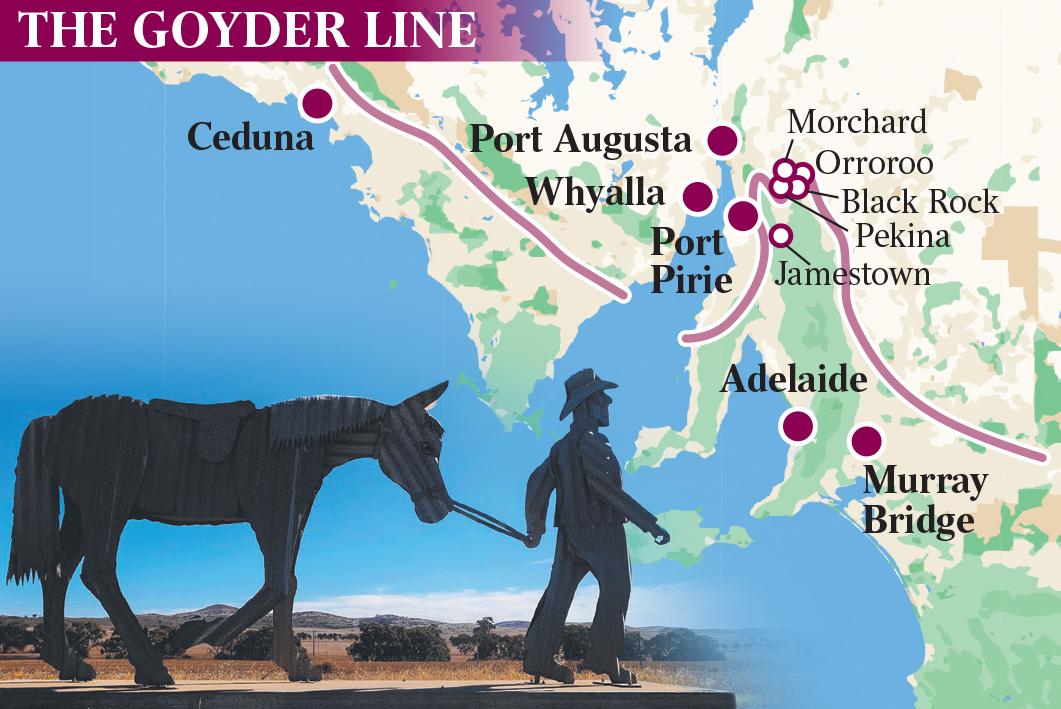

If there is one constant in a hardscrabble land of uncertainty it is George Goyder’s Line of reliable rainfall. For more than 160 years, the dots on the map that the colonial surveyor famously joined up in South Australia have defined where to crop and where not to, delivering a measure of order to farming in the driest state of the world’s driest inhabited continent.

Stay within Goyder’s Line and you had a fighting chance of bringing in a harvest before the heat of summer closed in. To plant outside it was to be perpetually at the mercy of drought or deluge – those binary extremes that mock every effort to tame the relentless cycle of boom and bust in the bush.

English-born Goyder understood this long before climatology became a science or the sophistication of Indigenous people’s light-touch land management was recognised. He traversed much of the Line’s epic length on horseback, meticulously plotting points of transition from one vegetation type to another, telltale of where the rain fell over an extended run of seasons.

The boundaries he set turned out to mirror with prescient accuracy the 250mm isohyet – a looping contour connecting places that receive the same average of annual rainfall across SA’s Mid North, in this case the bare minimum considered necessary to raise wheat and other cereal crops.

The technical achievement was mighty: Goyder drew the Line in the absence of the detailed weather observations and records we today take for granted. The lasting impact, though, was in the lived experience. His work all those years ago would shape the state’s development and land use policies.

Goyder’s method made sense of the chance-your-arm mayhem of farming on the margins in Australia, where centuries of learnings about raising crops under a gentle European sun had been rudely upended.

But what if even those givens were to change? If the once-dependable late autumn and winter rains became patchy, casting doubt on the time-honoured practice of waiting for Anzac Day to sow? If those bastard hot northerlies started to blow regularly in early spring, wrecking crops as they ripened?

When 43C-plus temperatures became the rule, not the exception, for the dog days of January?

Climate change looms as the killer variable Goyder couldn’t see coming. Out here, where dust devils dance like ghostly wraiths among the abandoned stone homesteads, the early settlers’ broken dreams echo in the ruins dotting a vast, tawny landscape.

Can their descendants’ grit and 21st century know-how somehow hold the Line?

It has been 15 years since we caught up with the Catfords, who have more experience than just about anyone of living and cropping in the state’s Mid North. Goyder’s Line runs along the bitumen road that divides the brothers’ properties outside sleepy Morchard, population 19, three hours’ drive north of the SA capital.

Gilmour, 65, and Rod, 68, are fifth-generation farmers whose connections to the area reach back to the mid-19th century.

Gilmour’s 29-year-old son, Andrew, is working with them after training as an agronomist, a sign of the times. When we last spoke in 2008, the outlook was grim. From central west Queensland, through regional NSW and Victoria, to the mouth of a stricken Murray River beyond Adelaide, the nation was in the grip of the Millennium Drought, one of the worst on record. Water levels in the Murray’s Lower Lakes fell precipitously, exposing acidic soil beds. There was speculation the Line could shift so far south that the vineyards of picturesque Clare Valley would be endangered.

Thankfully that didn’t happen.

Goyder’s Line runs along the bitumen road that divides the Catford brothers’ properties outside sleepy Morchard,. Picture: Matt Turner.

What changed most in the intervening decade and a half wasn’t so much the volume of rain, but when it fell. For farmers, the timing is just as critical as the rain gauge level. “We’re getting less rain when we want it most, in the growing season through May and into winter,” Gilmour says.

“To my mind … that is due to climate change. It’s made cropping more difficult when we don’t have irrigation here. It’s why there’s a lot more grazing happening – which is not optimal from our point of view, because it’s not nearly as profitable as cropping can be.”

Rod points out that good farmers adapt, making Australian producers among the world’s best.

It has always been a struggle on Goyder’s Line. As it happens, his property is just inside it, while the land Gilmour and Andrew work sits outside. Does it matter nowadays? “It’s definitely talked about,” Rod says, carefully.

Gilmour jumps in: “You know … they were cropping as far north as Farina,” a crumbling ghost town on the Oodnadatta Track, leading into the Sturt Stony Desert 400km away. “They had a couple of good years up there. They thought it was fine. Then drought set in and they lost everything. They walked away from their homes and the farms were turned into pastoral properties.

“The lesson is the further north you go, the more careful you have to be. Goyder’s Line isn’t definitive – people can and do make a go of cropping outside it – but as a marker it’s a very good guide to where you can expect to be successful over the long term.”

The effect can be quantified in the hard currency of property prices. The head of agribusiness development at Rural Bank, Andrew Smith, says the median value of farmland located inside the Line was, on average, 75 per cent higher than outside plots for the period from 2019 to last December. Interestingly, the gap had widened from the 68 per cent premium recorded between 1995 and 1999.

So, yes, where you farm in relation to the Line continues to count financially. “South Australia’s most productive farmland is typically tightly held and tends to change hands less often than in the less productive areas, which can drive competition from new buyers and farmers looking to expand existing operations,” Smith tells Inquirer. “The median price per hectare for the local government areas above the Goyder Line generally lags well behind those below the Line. The lower productivity potential of farmland in these areas has been well understood and priced into the market for many decades.”

But that’s not the whole story. Farmers get a say, too.

Better technology, new growing systems and increasingly drought-resistant crop strains have so far allowed them to keep pace with the altered conditions.

Andrew Catford doesn’t crop like his father and uncle did at his age. Fifteen years ago, the pros and cons of no-tillage cultivation were hotly debated whenever the local producers got together at one of the district’s then numerous pubs. Rather than plough in long furrows, breaking up the soil, the aim is to keep the surface intact to preserve moisture and the soil structure. Mechanical seeders use scalpel-like prongs to sow a crop with computer-enhanced fidelity; tractors are guided by GPS as much as driven. And then, come harvest time, a blanket of stubble is retained to insulate and nourish the paddocks ahead of the next production round.

These days there is no argument about precision farming – nor many places left, either, to have it out over a beer. Most of the historic stone-faced hotels have closed or trade for limited hours, reflecting the long, sad decline in the local population. “I don’t know anyone around here who hasn’t adapted to some form of no-till,” Andrew says.

The tiny town of Morchard – right on Goyder’s Line in South Australia. Picture: Matt Turner

An increasing proportion of planting is done “dry” – up to 70 per cent in the case of the Catfords – whereas traditional practice would be to wait until late April to sow in the hope of an autumnal soaking. Still, the earlier you get a crop in, the sooner it will get out of the ground and ripen, mitigating the damage a fiery gale off the desert might wreak in the spring. Equally, a hard winter could cause devastating losses to frost.

Juggling risk is a stomach-churning exercise for any farmer, weighing the weather and market forecasts with experience and gut instinct for what’s to come.

Alas, a crystal ball doesn’t come with the job.

Yet, as the young man explains, if there’s one thing worse than having your toil and hard-earned capital turn to dust, it’s failing to cash in on a rare time of plenty.

“You just have to be optimistic and assume it will rain at some point,” Andrew says. “It’s a lot worse to miss out on a good year than to scrape by when things are difficult. A good year or two can really set you up if you get it right.”

Jim Kuerschner used to work on the assumption there would be one good year in five. So how has that panned out?

“I can show you,” he says, producing a hand-drafted table of rainfall totals and crop yields back to 2009, following our last visit to his Black Rock property.

He’s a trim, 67-year-old who runs breeding ewes, cattle and raises wheat, barley and oats across 4400 hectares of undulating country with the help of sons Tom, 40, and Sam, 35. They’re the sixth generation of Kuerschners to take up farming: as we will see, family can be another factor in making it on the Line.

His best year for rainfall was 533mm in 2016, up 55 per cent on the long-run average for the farm of 342mm, followed by 426mm in 2020 and 419mm in 2009 after the Millennium Drought finally broke.

On the cropping side, the average wheat yield was 1.3 tonnes/ha, bottoming during the short, sharp dry of 2018 and 2019 (222mm, 155mm respectively) when barely a bag of grain came off the property.

Over the past 15 years, Kuerschner has had five crops yield above the norm, four on par and six below average, not bad all things considered. For the record, last year was poor, with the disappointing rain total of 270mm eliciting a commensurate dip in output. To date, a dry 2024 doesn’t promise to be much better.

Delve further into his figures, and the criticality of when the rain falls becomes apparent. In that bumper year of 2016, nearly two thirds of the total – 342mm out of 533mm – arrived in the key April-October window, delivering a wheat yield of 2.64 tonnes/ha.

The benefit was even starker in 2013 on marginally above-average rainfall. Fully 305mm of the 367mm fell during the growing season, delivering a bumper harvest of 2.22 tonnes/ha. If only you could bank on that from one year to the next. Kuerschner’s experience is that the winter rain is less reliable than it has ever been.

“The Line is such a rubbery thing,” he says, looking out over where Goyder superimposed it south of the homestead. “Wherever you draw a line on a map there’ll be good country outside, and bad country inside it. Nothing is a given and all you can try to do is be as efficient as you possibly can and grow when you can … because one of the key things in this country is economy of scale … you get bigger or you go out of business.”

His landholding is about twice what it was in 2008, a sign of his faith in the future, he insists. The irony is not lost on Kuerschner, a keen student of George Goyder’s life and times. Back then, free settlers were pushing deep into the SA interior in the naive belief that “the rain would follow the plough”.

Goyder, the son of a church minister who trained as a railway engineer before immigrating in 1848, had an inauspicious start as assistant surveyor-general when he mistook flooding in the great desert saltpan of Lake Blanche for permanent water.

By the time he embarked on his signature travels as colonial surveyor-general in 1861, wheat and barley were being cropped on the Northern Territory border, invariably disastrously.

In the teeth of another punishing drought, he was ordered to map “the line of demarcation between that portion of the country where the rainfall has extended, and that where drought prevails”. Goyder, who went on to survey the site of modern-day Darwin, hesitated to talk up the boundary as definitive, writing in 1868 that the Line “to a certain extent” separated agricultural and grazing lands.

But it had already taken on a life of its own. In the designated farming areas below the Line, sections of up to 130ha were auctioned on credit to settlers on condition that they farm the land – the idea being to encourage small, family concerns as a counterweight to the sprawling pastoral leases being consolidated through Central Australia.

In 1872, it became law: no agricultural grants were to be made outside the Line.

Naturally, a succession of productive seasons followed, precipitating a land rush. As memories of the hard times dimmed, Goyder continued to argue against farming beyond the Line, only to be howled down. No prizes for guessing what happened: drought returned and most of the incautious farmers who went north had to be relocated at yet more expense to the public purse. Their patchwork lots were absorbed in industrial-scale beef or sheep runs, defeating the purpose of the land reform program.

As Kuerschner notes, Goyder was largely right about where to farm, but dead wrong on how to go about it. Bigger turned out to be better because it is more efficient, and to crop successfully on the margins in Australia is by definition to do more with less. A lot less in the lean years. “We make do with second-hand machinery which we maintain ourselves,” he says, lauding his sons’ versatility. Sam is a boilermaker while Tom, a diesel mechanic, has his own earthmoving business, and both know their way around Dad’s cluttered workshop. “We’d love to buy new $1m headers or $500,000 tractors, like people do in the better areas,” Kuerschner says. “We just adapt and try to be resilient. You have to do things yourself.”

His neighbour, Kym Fromm, 67, another grower we met in 2008, is showing us around what’s left of his farm. A divorce put paid to his hopes of handing it on as a going concern to one of the kids; he leased the remaining 650ha to contractors, who are busy sowing in the late morning heat.

Kym Fromm. Picture: Matt Turner

The giant mechanical seeder is addressing the lightly turned earth, clanking to the distant fence line in a cloud of ochre dust. The creedbed that once cut the land has been filled in, giving the machine a straight shot from one end of the kilometres-long paddock to the other. “You want it as flat as you can make it, like a runway,” says Fromm, adding wistfully: “Nothing gets in the way of progress.”

Even so, he can still glimpse part of the vista Goyder would have encountered when mapping the central and best-defined section of the Line. From the west, it crosses the inside shore of the Eyre Peninsula approaching Moonta and rises to a W-shaped crest just short of Orroroo, population 516, not far from his farm. Continuing east, it falls away in a sweeping arc past Burra and Pinnaroo to the Victoria border.