Article by Brad Thompson courtesy of the Australian Financial Review.

Australia’s richest person has provided a rare insight into her initial struggles, motivations and ambitions after celebrating 30 years at the helm of what is now the country’s biggest private company.

It’s late January, and Tropical Cyclone Ellie has brought flooding to the Kimberley, damaging towns and closing essential transport routes.

Gina Rinehart – the country’s richest person with a $34 billion fortune, according to the Financial Review Rich List – is in Port Hedland with workers from her Roy Hill iron ore mine, about 180 kilometres south of Marble Bar, Australia’s hottest town.

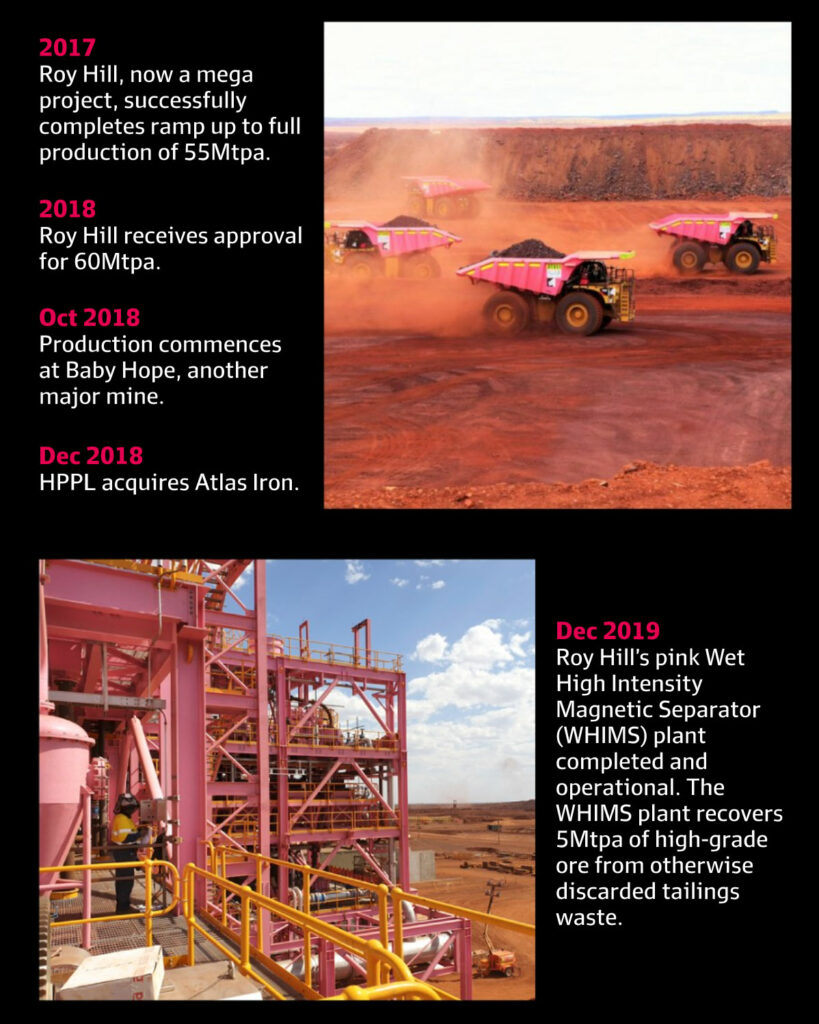

The event is to launch a campaign to encourage women in mining. Rinehart is in pink – so are the trucks at her mines, some of the plant and equipment, and the high-visibility safety shirts.

In an aside to her speech, she mentions that the next day her sprawling private enterprise will fly another plane-load of supplies to help the isolated communities cut off by the flooding.

There are no media people around and it is not a public event. Rinehart prefers it private – unlike some of her more fulsome positions on taxes, red tape and industrial relations that have made her a polarising figure in the last decade.

On her 69th birthday, Rinehart remains an enigma to observers despite being one of the country’s most prominent and successful businesswomen, with interests from iron ore to agriculture, rare earths to gas and even a stake in a medical cannabis operation.

In a written interview with The Australian Financial Review to mark three decades at the helm of Hancock Prospecting, Rinehart says she has no intention of slowing down and will continue to invest in iron ore, copper, lithium, gold and rare earths. She also remains open to acquiring other large, long-life assets.

She also shows no inclination to shy away from her outspoken views on government policy, whether it is the energy market intervention (doomed to fail) or the reintroduction of multi-employer industrial bargaining (taking the country backwards).

“Our investments are not driven by hype or by seeking taxpayers’ monies from governments,” she says of investments in green metals and oil and gas. “We know the law of supply and demand. It is fundamental – if supply falls, prices will rise.

“Governments stepping in to put in price limits on any commodity won’t increase investment in that commodity, and hence won’t increase supply of such commodities. Price limits may be seen as a temporary fix, but in reality, only make the situation worse, something we should learn from history.

“We continue to seek out Tier 1 assets, and would prefer to have the vast majority of our investment in Australia. Investment in Australia is what enables our high living standards; however, we must be mindful of government policies that make investment and development unattractive.”

It has been a busy few months for Rinehart, who this week succeeded in a lengthy tussle for gas producer Warrego Energy, helped by her fellow WA Rich Lister Chris Ellison.

Netball backlash

The businesswoman has also reshuffled her agricultural holdings and last year attempted to bail out the national women’s netball team (withdrawing her $15 million sponsorship after player backlash).

Those close to Rinehart say she is working around the clock and is involved in every part of the business despite the growing scale of the Hancock operations. Life in her inner circle can be gruelling and some fall in and out of favour.

“Extremely hard work got us to where we are and if we want to continue this success, then we need to remain vigilant and not let our success diminish our efforts,” she says when asked about her work ethic. “Mining is an extremely competitive industry, and Australia is a price-taker in the market, so we have to always be cost-conscious and performing productively.”

Acting Hancock Agriculture chief executive Adam Giles, a former Northern Territory chief minister, says Rinehart is the hardest worker he’s ever encountered. “Wherever she is and whatever is going on, she’s always working,” he says.

Another on her team puts it this way: “The business is her life, and she lives it every day.”

Giles says Rinehart doesn’t get enough credit for her business success, her quiet philanthropy and her generous support of Olympic and other sporting teams.

The proposed sponsorship of the Diamonds became a divisive issue last year after Indigenous player Donnell Wallam raised racist comments made by Rinehart’s father, Lang Hancock, in the 1980s. Other Rinehart detractors accuse her of using sports to soften her reputation as a controversial conservative who has made her riches from mining.

Her supporters, however, note that – like her breast cancer foundation – Rinehart’s sponsorship of sports such as swimming started in the 1990s when money was tight.

All her business achievements have been as a single mother, left widowed two years before the death of her father in 1992.

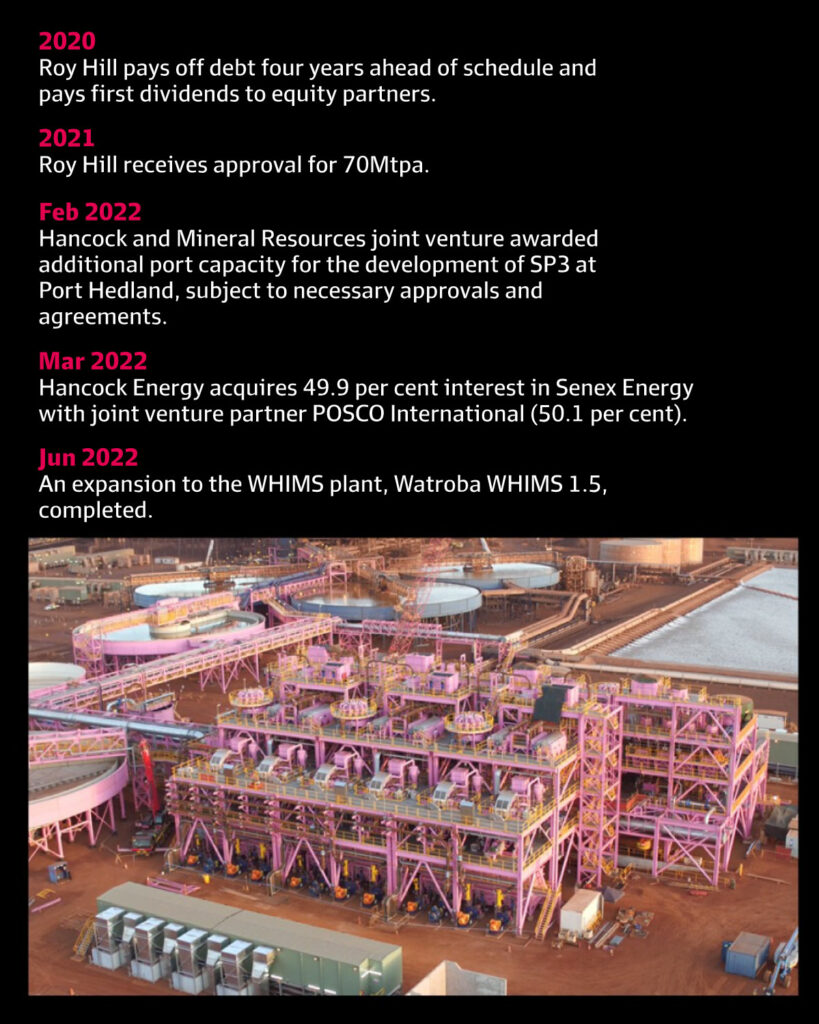

In 2015, Roy Hill became the first mega project in the male-dominated resources sector to be financed, built and run by a woman. Women now make up more than 25 per cent of the mine’s workforce. That’s ahead of the industry curve and growing. One video played at the January event with her workers was full of testimonies from women who had left jobs as nurses, hairdressers and beauty therapists for high-paying roles at Roy Hill.

And the mother of four is unfazed by what “greenies and fellow travellers” think of her. She is an unabashed fan of Donald Trump’s presidency, happy to invest in boosting domestic gas supply despite the rejection of the fossil fuel by conservationists and some fellow miners, including Andrew Forrest, and proud of her forebears and the role they have played in the history of modern Australia.

The “greenies and fellow travellers”, as she puts it, see her as a conservative dinosaur, stuck in the past, aloof and out of touch with modern Australia. There are headlines, sound bites and social media commentary that paint her as a mean mother based on an epic court battle with two of her children, a tyrannical boss who wants to pay workers $2 an hour and a mining heiress who owes it all to her father.

Her admirers within the workforce, on the other hand, see her as loyal, warm, engaging and generous. Insiders say she’ll talk to anyone during frequent mine site visits and company events. And, they say, traditional owners have also had a productive and respectful working relationship with Roy Hill and Rinehart’s broader Atlas iron ore operations.

The low wages claim still rankles Rinehart, who says: “I’ve never suggested we pay Australians $2 a day, that is just fake news, but I have pointed out that there are countries with minerals resources who were paying such very low wages, and we must compete against this to retain our markets; hence, government burdens must be cut.”

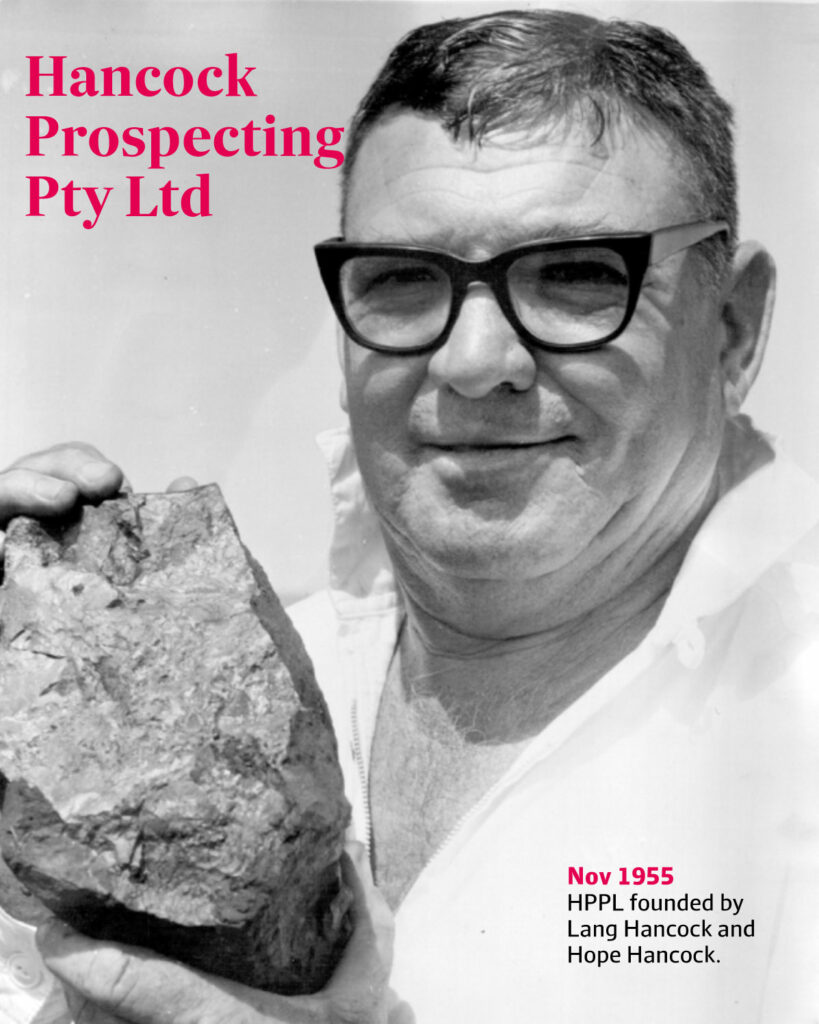

It could be argued that she owes her father, who never made the leap from prospector to miner, almost nothing in a financial sense after he left behind an estate that was eventually declared bankrupt following a legal battle.

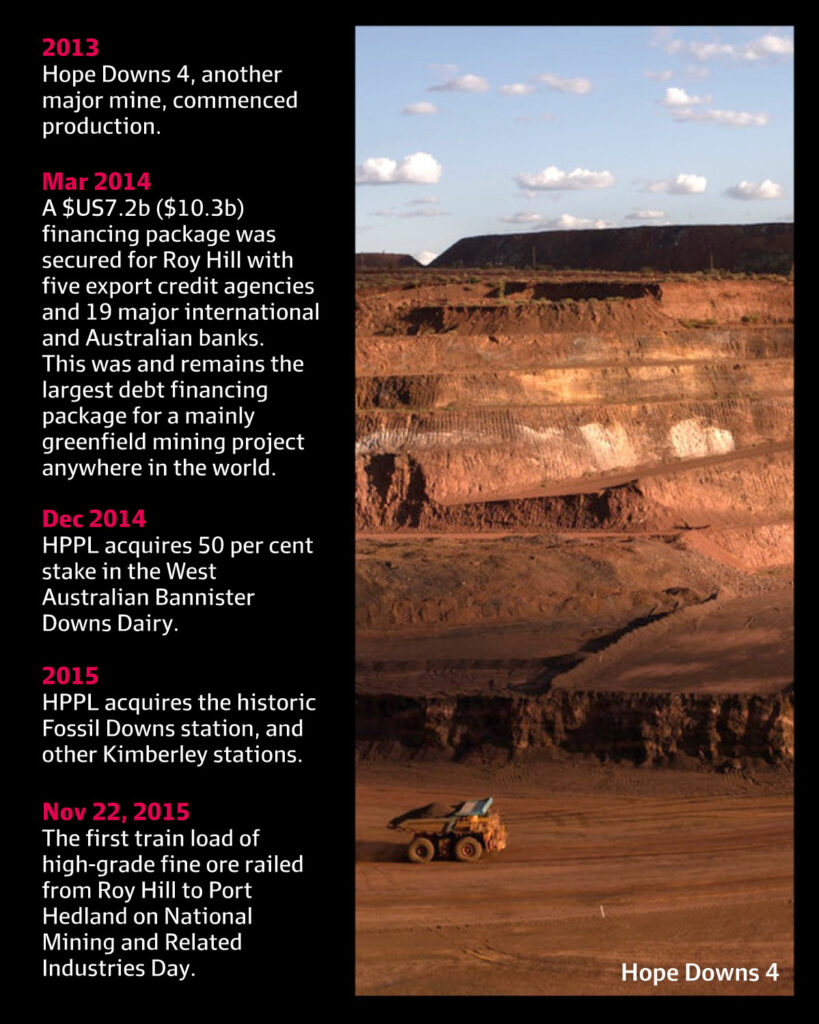

Things could not be more different now. Roy Hill exported slightly more than 60 million tonnes of iron ore in the 12 months to June 30 – a record, and declared a dividend of $3.3 billion to be shared among equity partners Hancock (with a 70 per cent stake), Marubeni, POSCO and China Steel Corporation. Atlas produced 9.8 million tonnes and delivered a $225 million dividend.

Rinehart also floated the idea of sharing profits – about 5 per cent – from Roy Hill with workers during a speech at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Perth in 2011 and long before it started shipping iron ore.

She has been paying out pre-Christmas bonuses to workers every year since 2018 to the tune of many thousands of dollars on top of the high mining wages. The day after the bonuses (in some years up to 30 per cent of annual base pay) were paid in December, Rinehart sprung a surprise giveaway at the Roy Hill Christmas party with 10 prizes of $100,000 each handed out.

Sources say Rinehart opted to keep drawing out winners until someone in the room won a prize and promised the cash windfalls would come in full and “after nasty tax”. Similar raffles for other arms of Hancock had prizes of $100,000 handed out in total.

‘It didn’t look as though we’d survive’

This week, she will randomly give away 41 prizes of $100,000 each to workers to mark her 69th birthday and will make the birthday and Christmas “Rinehart raffles” annual events. The 41 prizes represent one for each year Rinehart has worked at Hancock. The company has reserved the right to suspend future giveaways if the iron ore price falls below a certain point, but otherwise, raffles will happen at least twice a year.

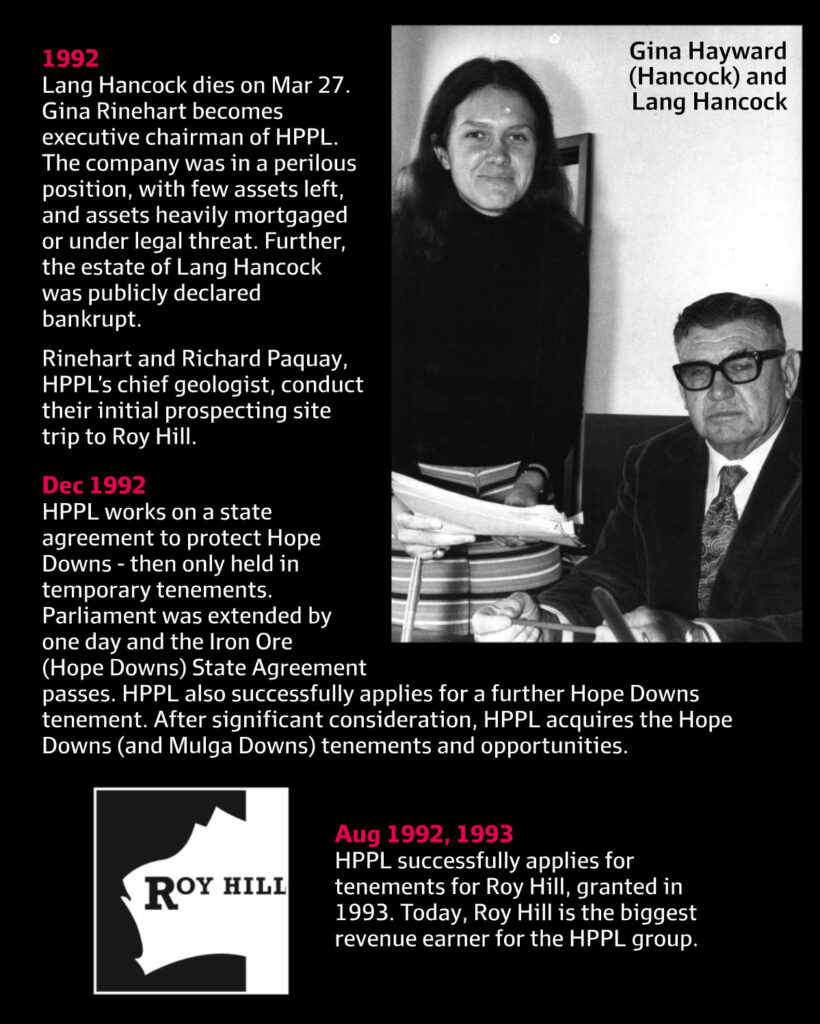

When, in 1992, Rinehart became executive chairman of Hancock, it was a company struggling despite all of Lang Hancock’s prospecting successes. A generous royalty deal from CRA that underpinned much of the Hancock fortune is now but a sliver of the wealth generated by Rinehart’s various ventures.

Rinehart says she has never forgotten those who stood by her, including Hancock executive director Tad Watroba. “In those early days when I became exec chair, it certainly didn’t look as though we’d survive 30 years,” she says.

“Few assets were left, and what was left was primarily either mortgaged or under legal threat.

“As I’ve told some people since we’ve been celebrating the past 30 years, cheques were being written and kept in the drawer so our then very small accounting staff could say they’ve been written, but we had to wait for the quarterly royalty before these could actually be mailed.

“It was extremely difficult in those early years, and I felt that my nose was only just above water level given the many significant problems our company faced. But it wasn’t just me not having it easy in those early years – my staff didn’t see bonuses or for some years, even pay rises.

“Tad in particular, also Terry (Solomon) and Richard (Paquay), very sadly both deceased, saw their mates go far ahead of them with salary and bonuses, but they remained loyal to me. I will never forget this.”

Hancock declined to make its top mining executives available for interviews, instead providing a copy of the speech Watroba gave at a private celebration to mark Rinehart’s 30 years as executive chairman.

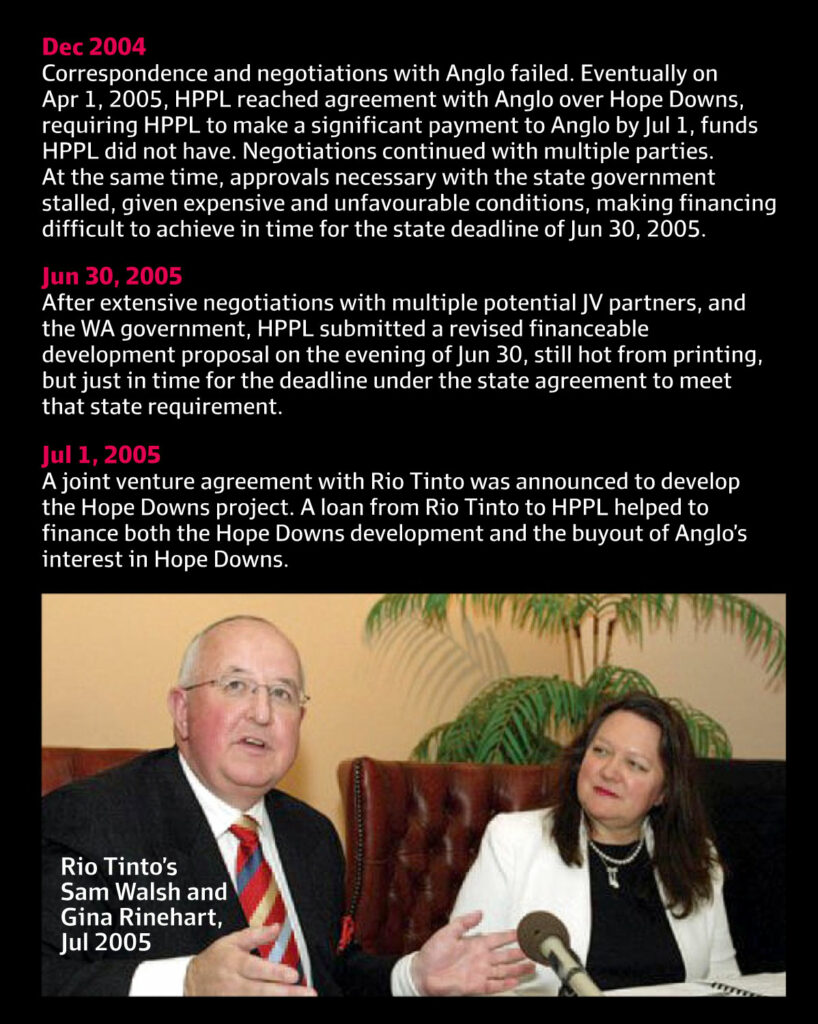

In his speech, Watroba detailed the journey from a struggling company and a pivotal moment when Rinehart opted to take on debt to push ahead with what eventually became the Hope Downs mines in the Pilbara owned in partnership with Rio Tinto.

“The first one [decisive moment] I remember, now probably a small step, but then an unprecedented one, was your decision to borrow some $20-25 million to speed up the Hope Downs exploration,” he told the event.

“In those days borrowing was not a company policy. Your decision changed the mentality of the team and gave an enormous boost to their confidence.”

Now, Rinehart faces another year of challenges to round out her 60s, including on the legal front. A court ruling last December paved the way for a long-awaited trial over the royalties that flow from the Hope Downs mines. The trial will pit Rinehart against Wright Prospecting, controlled by billionaire Angela Bennett and two of the daughters – Leonie Baldock and Alexandra Burt – of her late brother Michael Wright.

The Rinehart camp had tried to have the trial pushed back pending the outcome of arbitration between Rinehart and two of her children, Bianca Rinehart and John Hancock. The pair are involved in arbitration with their mother over a family trust that has billions of dollars sitting in limbo. The arbitration revolves around a trust that holds a 23.4 per cent share in Hancock on behalf of all four children.

In a statement issued with Hancock’s latest financial results, the company detailed discretionary dividends paid to the family members, including more than $1 billion in 2022, and almost $4.8 billion is held in reserve amid the legal dispute.

With such high stakes in both cases and scope for appeals and further legal action, it appears unlikely that the matters will reach their conclusion this year.

Mining backlash

One chief worry for Rinehart, she says, is growing anti-mining sentiment. “Unfortunately, there are many anti-mining people and fellow travellers who fail to realise the vital nature of what our industry provides,” she says.

“There are some people who would be happy to see our industry shut down, but would they be happy to give up their phones, homes, iPads, cars, electricity, hospitals, bridges, trains, buses, planes and more?

“Mining touches every part of our lives every single day. Electricity touches every part of our lives every single day. And if we are to work towards the currently stated goals of our government, mining will only become more necessary.

“For example, a typical electric car has six times more minerals and metals than the typical internal combustion car, and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant of the same capacity.

“Our governments want us to move from a fuels-intensive system to a system that is required to be more minerals-intensive, but they appear to welcome policies that do not want us to invest in and develop the necessary mineral resources to do this.”

Rinehart says politicians need to have a better understanding of the mining industry and energy supply.

“We wouldn’t have the country we have without the mining industry, and reliable energy supply. We simply wouldn’t have the funds for our hospitals, aged care, police, critical defence, emergency services, kindergartens and more, if it weren’t for the resources industries,” she says.

“Not only do we provide the raw materials needed for all buildings, electricity, machinery and defence equipment, and more, but we also provide enormous tax and royalty payments to government to pay for these things.

“In a time when successive governments have overspent so that we are now in record huge debt, what our governments should be doing is reining in their expenditure and size of government, and urgently and significantly cutting its [red] tape and approvals, so Australians can move forward and can maintain our living standards.”

It is typically blunt advice from a woman who carries with her the memories of much tougher times. Speaking to the Roy Hill workers that January evening, she recounted something of her family history. It was three members of the Hancock family that set off on a small wooden boat, the Sea Ripple, sailing north-west to the first Pilbara port, Cossack.

“Fanny was still only a teenager, Emma had a child and was expecting another, she was 21 when they set off into the remote unknown,” Rinehart told her workers.

“When the Hancocks arrived, they had lost most of their supplies, possessions and stock during the voyage and had to walk about 14 miles inland to find fresh water, founding the first township at what is called Roebourne. No kitchen, bathroom, electricity, plumbing or air conditioning, no home, no shops, no fruit or vegetable garden, no medical facilities, no take-out greeted them, they had to make do for themselves, or do without. No entertainment either, just work to stay alive and provide for their growing family, day in, day out, except on Sundays, when they took time off to read the Bible together.

“In my view, these stories should be passed along to our families, to help put our daily stresses and problems in perspective, and give inspiration, especially to our young, if not by teachers, then by families.”